In this conversation with Neville Page, we sat down to discuss his two new Gnomon Workshop titles, Virtual Makeup Design: Volume 1 and Volume 2, and his upcoming book, Beauty in the Beast — a deeply personal field guide to surviving and thriving in the entertainment industry.

What follows is more than a breakdown of tools and techniques. Our conversation became a rich exploration of process, practicality, mindset, and how artists can better align creativity with production reality.

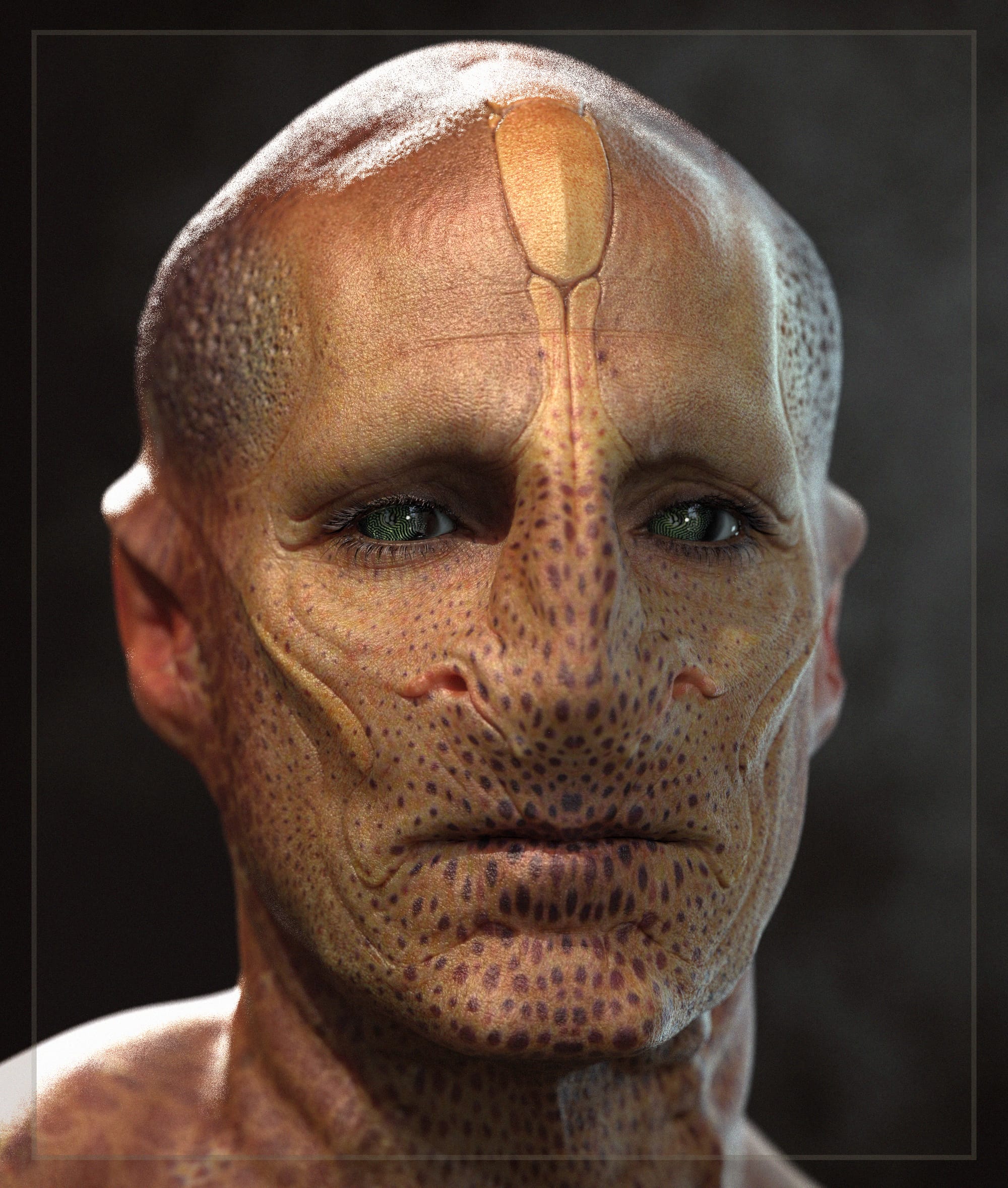

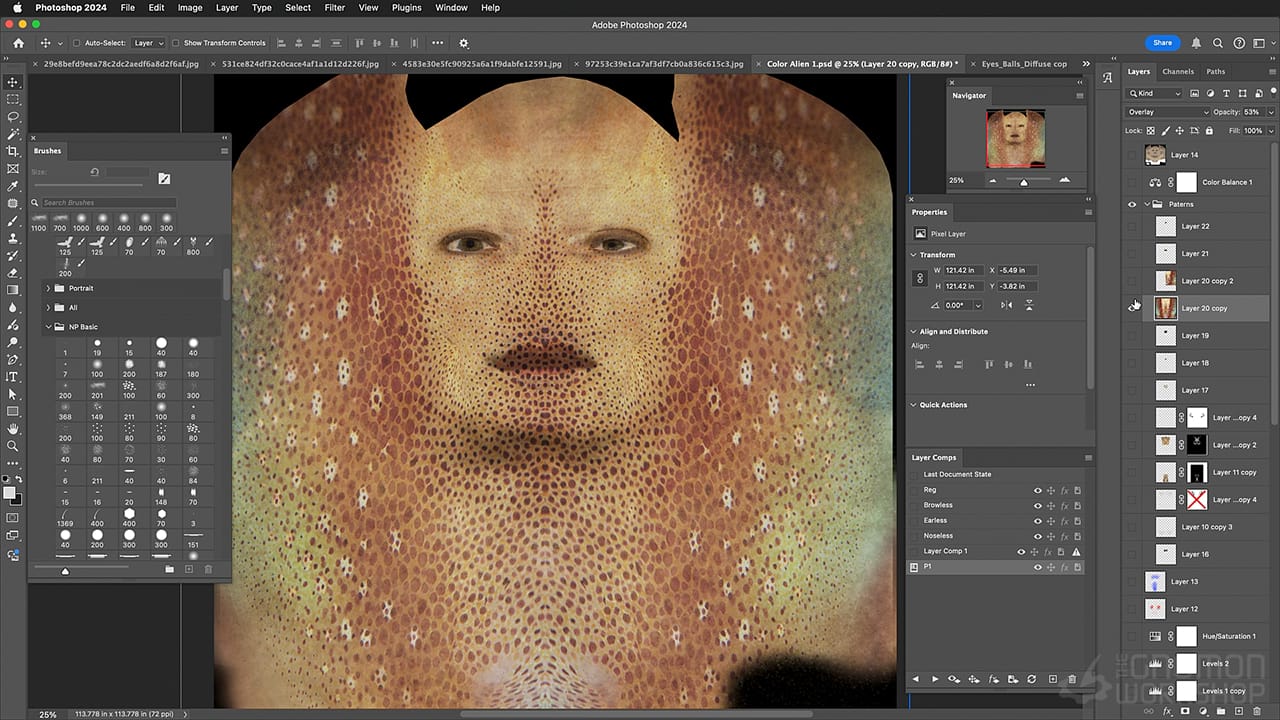

Alien virtual makeup design series by Neville Page. Learn Neville's complete design process at thegnomonworkshop.com

The Gnomon Workshop: To kick things off, could you briefly introduce yourself in your own words?

Neville Page: My name is Neville Page, and I’m a concept artist in the entertainment industry, as well as a teacher. Over the past ten years, I’ve also been producing, directing, and writing.

TGW: You’ve got a lot happening at the moment: two new Gnomon workshops and what looks like a very personal book on the way. What’s been fueling this creative fire lately?

NP: It’s actually been burning for quite a while. When it comes to education, like these Gnomon Workshops, I’ve been involved with Gnomon for a long time. Not quite since the very beginning, but pretty close. In fact, the very first workshops I did with Alex Alvarez, the founder, were held at his house. So, yes, it was definitely a while ago, and I still had hair back then! It’s been a minute.

I’ve always been passionate about teaching and education. I’ve taught formally at a number of different colleges, including Gnomon, so that interest has always been there. But the time? Not so much.

The opportunity arose when the film and TV industry began to slow down, due to a combination of factors: COVID-19, strikes, wildfires, and other contemporary challenges. So with that downtime, I turned my attention to other creative pursuits. I was doing a lot of IP development, scriptwriting, and directing, and working with a company called Orbital Studios that specializes in virtual production. We’ve done a few projects together during this period.

But I also thought: Now I finally have time to get back to my book, Beauty in the Beast, which I’m a little embarrassed to say I started over ten years ago. And by “started,” I mean a bunch of false starts. I’d think, I’ve got a couple of months off between films — I’d start it, and then a project would come up, and I’d be either obligated or genuinely excited to jump back in.

The Gnomon Workshops — Virtual Makeup Design, Volume 1 and 2 — also came into the mix at this serendipitous moment. I had the time, and The Gnomon Workshop had an interest in doing something new. I had already begun developing chapters around the idea of virtual makeup for the book, so Alex and I talked about that as a potential workshop topic. It resonated, because even though Gnomon doesn’t offer classes in makeup specifically — and I’m not a makeup artist myself — I am a designer of creatures and characters.

So, these workshops are helpful whether you’re purely interested in design or if you’re into ZBrush and want to see how it fits into a specific pipeline. And if you have an interest in virtual makeup — or at the very least in designing for virtual makeup — it’s a great fit. It’s also a pretty unique approach to design, because it’s so specific: You’re designing makeups that actually need to work on a real human, rather than just on a digital character driven by performance capture or newer tech.

This whole concept really came from my experience on Star Trek Into Darkness with J.J. Abrams. That was the project where I had a kind of personal eureka moment, realizing that designing this way could genuinely help a production. So that’s the origin story behind it.

Renders of Neville Page's Lizard makeup design as featured in his Gnomon Workshop tutorials, streaming now at thegnomonworkshop.com

TGW: Virtual makeup design feels like something you’ve really helped define over the years. Would you say you’ve played a key role in how the industry has come to understand the process of designing makeup digitally, so that it can then be applied practically?

NP: You know, I never like to plant my flag in the sand and claim ownership of something, but I was definitely there at the beginning of this movement. It’s possible that I was one of the first to start designing this way.

It’s a bit like when 3D scanning first became viable for toy design. Years ago, when scanning finally reached a resolution that was useful, I was working with a company called Gentle Giant, run by Karl Meyer. Karl and I became friends because we shared similar interests — we were both working in the toy industry. Gentle Giant was creating a lot of toy sculptures, and I was also involved in that world. I was just returning to LA after teaching in Switzerland, and before that, I’d been in San Francisco — so when I came back to LA, years had passed, and I didn’t know anyone anymore. I had no social network, in the literal sense.

I got offered a sculpting job, but didn’t know how to sculpt in wax. So I called a friend who was working with Mattel, and through a few connections, I was put in touch with Karl. At the time, Gentle Giant was essentially his garage, and he had a wax recipe — something like Mattel’s secret formula — and he was kind enough to share it with me. He gave me some wax, some tips, and told me what tools to use. He was incredibly generous. As a teacher myself, I think generosity is essential. You can’t “own” a technique or approach. It’s not about what kind of pencil or paper you use. It’s about sharing the wealth.

That job led me to sculpting for Jakks Pacific, and I did a ton of likeness sculpts for WWF — now WWE — which was a fascinating chapter in my career. Around that time, Karl was experimenting with head scans, and I started connecting the dots. I realized I was constantly having to make revisions to wax sculpts — painfully slow revisions. The worst was when a client would ask, “Can you make this 5–10% bigger?” which is effectively an entirely new sculpt. You can’t just stretch wax.

I already knew about ZBrush, scanning, and other tools, but they weren’t being used together yet. So I asked Karl if he’d share one of his head scans with me so I could play with it and present a new approach to the client. I knew that by doing this, I was essentially proposing that they shift away from traditional sculpting and toward a digital pipeline using scans, which made business sense for them, but not for me! I didn’t have a scanner or the necessary tech. Still, I explained the benefits: “You want something 5% bigger? Done. You want it taller, moved, or mirrored? Easy. Digital is much more flexible.”

I explained it so well that…I lost the job! But honestly, that was okay. It made sense. I didn’t feel like I was shooting myself in the foot. I felt like I was doing the right thing. It would’ve been disingenuous to withhold something better just to protect my own position.

The reason I bring all this up is to show how important it is to recognize when you’re at the front edge of something, when you can combine tools or processes in a new way. That same mindset carried over into my work years later, around Avatar and then Star Trek Into Darkness, where I realized ZBrush and digital sculpting had evolved enough to support actual production.

By the time I was working on Into Darkness with J.J. Abrams, we already had a few films under our belt and a good working relationship. I felt comfortable saying, “Hey, can I show you a different approach?” — one that didn’t involve pencil drawings or clay maquettes. Although those are 100% still valuable, by the way. I still encourage artists to learn those skills. But I wanted to surprise him with something I believed had more practical value for that project.

This approach actually began earlier, on Super 8. On Super 8, I had the experience of presenting a digital creature not as a gray sculpt, but as a fully painted, textured, and lit version, lensed the way it would appear in the film. I even spoke with Larry Fong, the DP, to understand how he planned to shoot it — how much smoke there would be, what kind of lighting. I replicated all those elements so that when J.J. saw the design digitally, it felt fully contextualized. That made the approval process much faster and much more aligned with production.

So when we got to Into Darkness, I applied the same philosophy to makeup design, specifically for the Klingons. Instead of sculpting a generic head, I used a scan of my own head and fully resolved the design using Modo. I carefully mimicked silicone makeup materials, using subsurface scattering and other techniques. I even lit the render to match the actual set, since I had access and could take reference photos.

When I presented the design to J.J., he actually asked if it was a makeup test, because it looked so realistic. That was the moment I realized this method really worked. He was able to say, “That’s exactly what I don’t want,” because he wasn’t looking at a suggestion or a sketch. He was seeing the thing itself. Furthermore, because it was on my face, and we didn’t have the actor cast yet, he could look at the render, then look at me, and evaluate how buried the actor might be in makeup, or whether their features would still be visible. And depending on the character, either outcome could be ideal.

That was the moment it all clicked. This was a viable process for approvals. And yeah, it was quite a while ago — before a lot of people were doing this kind of thing. So I’ll go as far as to say: I was using it before most people. But I won’t say I invented the process. All I did was use existing tools, created by others, and combine them in a way that helped production.

Like they say, necessity is the mother of invention.

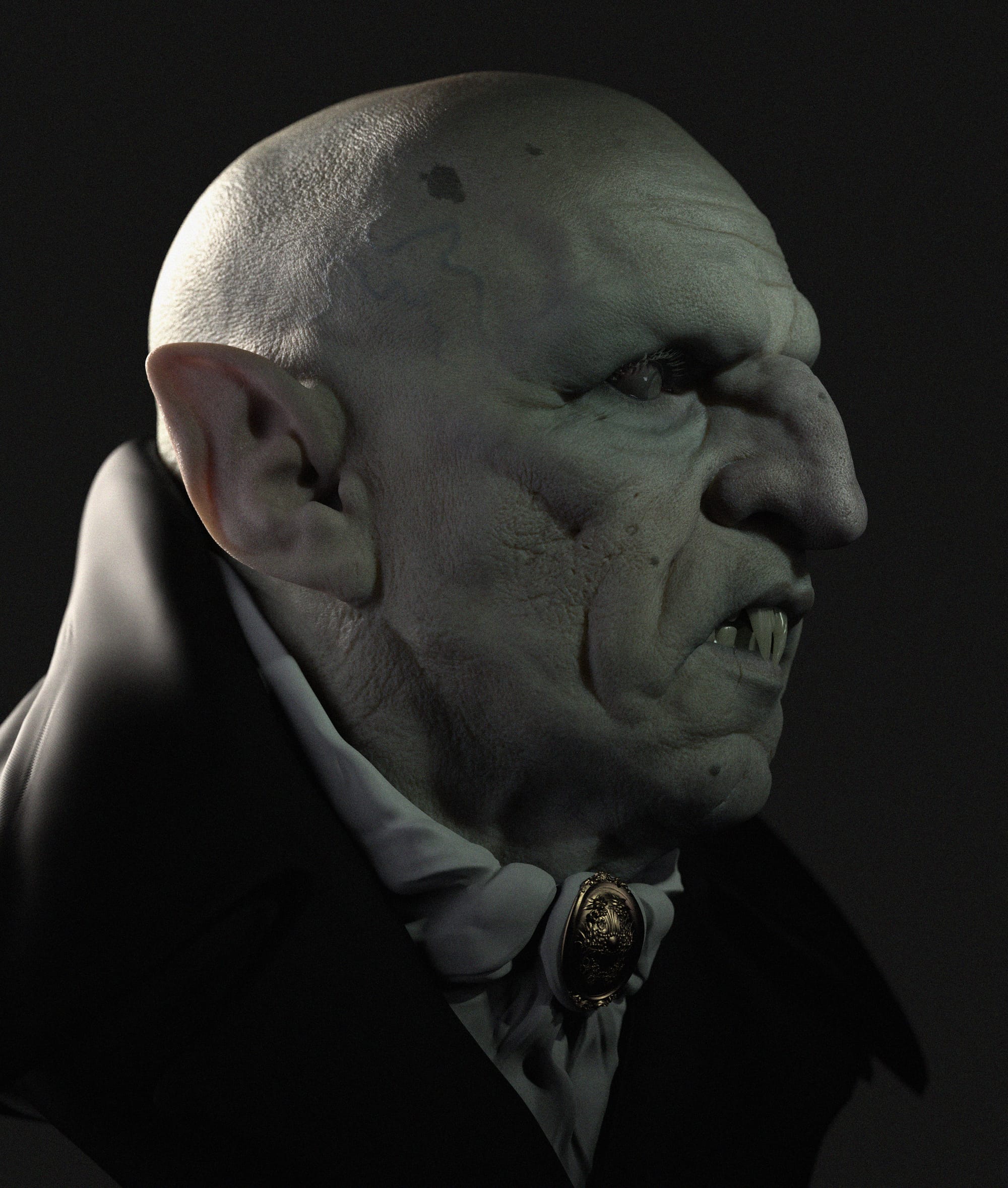

Neville Page as a vampire; learn how Neville designed this character's makeup in his new tutorials at thegnomonworkshop.com

“I remember on Avatar, James Cameron approved a design. Later, some of us in the art department, thinking like typical artists, tried to refine and improve it. When Jim came back, he said, “What happened? Your design has drifted.” Those were his exact words. I thought, No, I just made it better! But he said, “I approved it once. That’s what I wanted. Don’t change it. It was a big lesson: Some directors, like Jim, don’t want things to evolve past their point of approval. They want exactly what they signed off on—that image you initially delivered.” Neville Page

TGW: Would you say that virtual makeup design has become more common now in films that use practical makeup? Is this process used widely in pre-production?

NP: It’s being used more, but I’m surprised it’s not as common as it could be. That’s partly because different departments operate in different ways. The concept art department usually doesn’t include creature designers. And when you think of a traditional film makeup department, it’s often focused on beauty makeup or aging effects, not the creature design side of things.

Specialty shops handle creature work — places like Rick Baker’s old shop, Alchemy Studios, or Vincent Van Dyke Effects. There are many out there. When I worked with Joel Harlow, prosthetic makeup supervisor on Star Trek, he and I developed a strong working relationship. We both saw the value in close collaboration: Me as the designer, and Joel as the head of the creature makeup department. I learned a lot from working with him, and dare I say, he may have picked up a few things from my design approach as well.

At the time, there weren’t a lot of digital sculptors in makeup. Photoshop, yes, but not much digital sculpting for practical makeups. It’s a tricky thing. You have to weigh whether it’s worth the expense for a makeup department to hire someone who can digitally sculpt in ZBrush. You also have to consider whether it’s worth it for a traditional sculptor to make the transition into digital.

Over time, it’s been happening more and more. Shops like Legacy Effects — formerly Stan Winston Studios — are full of incredible digital artists. They’ve really embraced ZBrush and innovated with it. Even smaller boutique shops, like Vincent Van Dyke Effects, are incredibly forward-thinking.

When Vincent and I worked together on Star Trek: Picard, designing the Borg Queen, we had an opportunity to push things even further. We weren’t just using virtual techniques to present ideas to clients — we were actually using them to fabricate elements of the makeup. What we did with the Borg Queen was new: We 3D-printed the hard pieces of her crown and even printed pieces that would later be molded and cast in silicone or latex.

Today, the next evolution is happening: Instead of printing rubber parts directly, which still isn’t perfect, you can now print the molds themselves. You design digitally, print the mold, and cast the final material from that.

But here’s the key: As a designer, you have to understand both the aesthetic and the technical requirements. It’s not enough to just make a cool shape — you need to ensure the piece can function practically in a makeup department. And for shops that are willing to invest in this kind of hybrid workflow, it’s a real advantage.

If you stay up to date with new materials, 3D printers, and evolving techniques, you stay relevant and employable. That’s something I talk about a lot: there’s no point in hoarding knowledge. I’ve learned so much from others—whether they knew they were teaching me or not—that I feel strongly about sharing everything I know.

All of this relates back to the workshops. In my Gnomon Workshops, I teach a technique that has far more potential if you keep learning, and which will help you bring your digital designs to life. And that’s incredibly powerful for clients.

After all, when a client approves a traditional drawing — say, something done in graphite — they like the design, but then it goes through several hands: The sculptor, the mold-maker, the makeup artist. Each stage can reinterpret and change the design. By the time it’s glued onto an actor’s face, it may look very different from what was initially approved.

Sometimes change is necessary. However, preserving the original intent can be just as critical. I remember on Avatar, James Cameron approved a design. Later, some of us in the art department, thinking like typical artists, tried to refine and improve it. When Jim came back, he said, “What happened? Your design has drifted.” Those were his exact words. I thought, No, I just made it better! But he said, “I approved it once. That’s what I wanted. Don’t change it.”

It was a big lesson: Some directors, like Jim, don’t want things to evolve past their point of approval. They want exactly what they signed off on — that image you initially delivered.

So if you can present a client with a final, fully realized version of a design, and they approve it, you’ve made the entire process much smoother. You protect the integrity of the original idea and help the production tremendously. The skills needed to achieve this are precisely what I focus on and share across both volumes of the workshops.

“When you’re world-building in a science-fiction film … You need to define things like the air density, because that dictates the size of wings a creature needs to fly. You think about what the creatures eat to figure out their teeth. You think about the ground they walk on to determine the shape of their feet. The rules help you create something plausible.” Neville Page

TGW: You’ve touched a lot on creating a final, production-ready design — but even earlier in the process, when you’re just sculpting in ZBrush, how much does real-world awareness shape your creative decisions? Knowing your designs will ultimately have to be made in latex, silicone, or other materials, do you find yourself needing to restrain your imagination? Or can you still let it run wild?

NP: That’s a great question, because it touches on something I encounter a lot: The idea of restrictions, or feeling like creativity is being held back.

Sometimes when you start a project — whether it’s a building, a creature makeup, or even a piece of music — you’re given parameters. And for a sensible artist, parameters aren’t limitations; they’re the definition of what you’re supposed to create.

For example, if someone says, “You get to compose a piece of music,” you might immediately imagine working with the London Symphony — full orchestra, strings, brass, the works. But then the client tells you, “Actually, it’s just a quartet. It’s meant to feel very intimate.” If you’re not a mature, seasoned artist, you might think, You’re restricting me! You’re holding back my creativity! But really, those parameters are the rules of the world you’re building within. They’re what guides you.

It’s the same when you’re world-building in a science-fiction film. You need to define things like the air density, because that dictates the size of wings a creature needs to fly. You think about what the creatures eat to figure out their teeth. You think about the ground they walk on to determine the shape of their feet. The rules help you create something plausible.

So, when I’m told a makeup design is going to be applied to a particular actor, I study that person. And it matters. Sometimes it’s measurable, like the distance between their eyes, or sometimes it’s just perceived based on the structure of their nose and face. Some people appear to have closely set eyes. If you’re adding thickness to the nose with prosthetics, the eyes can quickly start to look cyclopean — and not in a good way. That’s not a creative “restriction,” it’s just a reality you have to design around.

Personally, I like rules and boundaries. They create an artistic challenge. They also give you a starting point, because when you have no rules, no budget, no limitations, it can actually be overwhelming. That blank white sheet of paper can be the hardest thing to face.

As for material choice — whether something will be made from silicone or latex — it doesn’t always impact the early design stage unless you’re creating a fully rendered, virtual makeup. In that case, material matters a lot. Light reacts differently to silicone than it does to latex. For example, if you’ve got large ears that will be backlit, silicone will create beautiful, realistic translucency with a reddish glow. Latex won’t behave that way; it absorbs light differently.

Material choice also affects movement. Latex moves differently than silicone, and if there’s going to be a lot of motion — say, around the mouth or eyes — you need to factor that in, even at the design stage. You might be proposing a design solution that later becomes a technical requirement for the makeup department.

And there are other factors you have to think about, too — things you only learn with experience. For instance, who’s wearing the makeup? Are they claustrophobic? Have they just had a baby and don’t want to sit for long application and removal times? Are they someone who hates heavy prosthetics? You start asking these questions, and sometimes your client is surprised, like, “Why are you asking me that?” It’s because every answer affects what you can realistically design for them.

It all ties back to something I call Honest Design. If you design something that makes the client say, “That’s amazing!” but the actor later refuses to wear it, or the makeup team struggles because it’s impractical, then you haven’t designed honestly.

Sometimes, concept artists will design these crazy, intricate patterns, pulling from animal references that look incredible but are basically impossible to paint and maintain every day on set. It’s easy to sell those ideas because they’re new and visually striking. But if the practical team isn’t given the time, budget, or tools to pull it off, it’s profoundly unfair. And it’s a dishonest design, because you didn’t deliver something manufacturable.

TGW: Your workshops cover a lot of valuable technical skills — sculpting, lighting, rendering — but it also feels like you’re really keen to impart the mindset of a designer. That practical and emotional awareness seems just as important in what you’re teaching. Would you agree?

NP: Yes. I always include this thinking in my tutorials for two reasons. First, and most importantly, I feel that those kinds of insights are so valuable that not including them would be leaving out a crucial part of the full picture.

The second reason is a bit more practical: There’s a lot of downtime when you’re making these kinds of workshops. Sculpting, painting — whatever the activity is — it takes time. Even when you speed up the footage, you eventually run out of things to narrate. You can only say, “Here I am still sculpting the bicep,” or “Still painting the eye,” so many times before it gets repetitive.

So, for me, the filler becomes story time. I use that space as an opportunity to share experiences and ideas. I try to keep those stories relevant to what I’m doing — sometimes directly connected to the sculpting or painting I'm working on. Other times, I’ll go on a tangent and talk about an experience I had on a film that might not directly relate to painting an iris, for instance, but will be entirely relevant to the artist who’s seeking to learn and grow. You never know who might actually want to see those small moments — someone might want to slow it down or pause and really study that subtle detail. So instead of cutting it, I fill that space with what I like to call Bonus Content. It’s not what the workshop is primarily about, but it’s an extra value for the viewer.

To be continued... In Part 2 of our interview with Neville Page, we explore his deeply personal book, Beauty in the Beast, and find out how artists can stay grounded, curious, and resilient in an age of AI and uncertainty.

Neville’s new workshops, Virtual Makeup Design: Volume 1 and Volume 2, are now available at Gnomon Workshop. Whether you’re looking to level up your sculpting, rendering, or presentation skills, they offer a detailed look at the professional techniques behind production-ready design.

To go deeper into the mindset, resilience, and creative philosophy that have shaped Neville’s career, you can support his upcoming book, Beauty in the Beast, on Kickstarter. It’s more than a collection of creatures: it’s a manifesto for staying curious, evolving with the times, and creating with intention in a changing world.

→ Watch Neville’s workshops at gnomonworkshop.com

→ Support Neville’s book, Beauty in the Beast, on Kickstarter

The Gnomon Workshop

The Gnomon Workshop, the industry leader in professional training for artists in the entertainment industry.

follow me :

Related News

Beauty in the Beast: Neville Page on Burnout, Mindset & Creative Survival

May 07, 2025

Capturing Assets & Environments for Call of Duty: An Interview with Gui Rambelli

Feb 10, 2025

Balancing Elegance with Aggression: An Interview with Chris Beatty

Nov 21, 2024